The College at Old Westbury was conceived in the midst of the late twentieth century’s democratizing of higher education. In 1900, only two in one hundred Americans attended college. Rates increased gradually, but college graduates remained a distinct minority. After World War II, the GI Bill expanded access to college in the postwar era; college was no longer a bastion of economic elites. The Cold War also increased the numbers who attended college, which led the federal government to invest heavily in universities, strengthening ties between the state, industry, and the academy. Strong support across the political spectrum led to legislation such as the National Defense Education Act of 1958, the 1964 Economic Opportunity Act, the 1965 Higher Education Act, and then the Basic Education Opportunity Grant of 1972 (now called Pell grants). This legislation enhanced citizens’ chances of attending college and nurtured university research and innovation. Individual states also expanded their university systems, constructing hundreds of new campuses.

The State University of New York (SUNY), with sixty-four campuses, is today the largest university system in the nation, despite getting a late start. Unlike other states that utilized Morrill Land Grant funding (1862) to establish or strengthen flagship universities, in New York such funding went to the private Cornell University. Not until 1948, under Governor Thomas Dewey (1943-1954), was SUNY established by bringing together twenty-nine colleges, eleven of them “normal” or teaching colleges. New York was the last state to create such a system. But Governor Nelson Rockefeller (1959-1973), a politician of grand ambitions, succeeded, as he vowed, “to build the world’s largest and fastest growing State University.” Under Rockefeller the student population grew nearly tenfold, and the number of campuses almost doubled.

First proposed in 1964 along with Purchase in Westchester County, the College at Old Westbury was designed to meet the needs of the metropolitan New York City area. The Old Westbury experiment began in an unlikely spot—the former estate of a Singer sewing machine heir, F. Ambrose Clark. The Gatsby-era grounds included a forty-three room, nineteen fireplace mansion, three sets of stables, multiple cottages and six other buildings, including a home for Clark’s disabled daughter. The stables were to hold the first classes; architects would place the college on the steeplechase course. The Clark’s gatekeeper remained working on the site through the College’s early years.

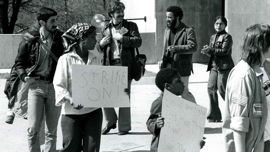

Two years later, when the College began formal institutional planning in 1966, SUNY shifted the college’s mission to address the alienation of a contemporary, bureaucratic society. External events pushed the Trustees and Chancellor in this direction. Early in the 1960s students had been perceived as conservative and compliant. In 1959, Clark Kerr, then head of the University of California system famously said of college students, “…They are not going to press very many grievances, there won’t be much trouble, they are going to do their jobs, they are going to be easy to handle. There aren’t going to be riots. There aren’t going to be revolutions….” Kerr misjudged. Beginning in 1961, African American students invigorated the modern civil rights movement in sit-down protests at Southern lunch counters—often under the gimlet eye of college administrators who expelled them for their activism. Southern and Northern students joined together to challenge white supremacy with Students Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and other civil rights groups. Not long after, student activists created Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). SDS fought racism, economic injustice, the atom bomb and they sought to counter the depersonalization of the world they lived in. They rejected the American Dream of their day, they did not want to be “organization men” working as technocrats or bureaucrats in white-collar positions. Instead they aspired for citizens’ active and direct decision-making in their own lives. In California’s flagship, UC Berkeley, students resisted administrators attempt to restrict their fundraising for SNCC, giving rise to the 1965 Free Speech Movement.

College administrators, students, and faculty all believed that Old Westbury’s unusual mandate was SUNY administrators’ response to this growing discontent. The mission statement criticized “the lock step march in which one semester follows after another,” maintaining such an education “consumed” college-age youth. The SUNY trustees instead encouraged students’ “full partnership” into the “academic world” through an experimental curriculum. Some believed the College offered an innovative way to engage students and facultyand break down traditional educational frameworks; others thought the College was meant to siphon off and contain student activism.

To lead the College, SUNY planners hired civil rights attorney Harris Wofford, a student of Gandhian non-violent civil disobedience, advisor to Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy, and a pioneering Peace Corps leader. Wofford had SUNY’s full support and he brought in educational advisors such as the noted sociologist David Riesman to help plan the college. Unusually, students themselves, even high school students, participated in the planning of the college. Debate over the college’s direction—the curriculum, including independent study and community action education, student body composition, appropriate pedagogy, faculty hires and even the college’s structure—was vociferous from the beginning, and grew in intensity even as the college opened its doors, in September 1968, with a pilot class of fewer than one hundred students.

1968 was a volatile year, as the youth activism of the early 1960s had reached a boil. In 1967, at the University of Wisconsin, students struck against Dow Chemical’s connections to the University and its involvement in the Vietnam War—in 1968 there was a firebombing there. At Berkeley students held a sit-in that spring, demanding an ethnic studies curriculum, a diverse faculty, and more third world students in the classroom. At nearby San Francisco State University students organized a student strike—the longest ever—for the same goals. Closer to home, in the spring of 1968, students occupied multiple administrative and classroom buildings at Columbia University to protest Columbia’s relationship to African Americans in nearby Morningside Heights and for their research participation in the Vietnam War. New York University had its own general strike in the fall of 1968.

With less institutional history, and only short-term ties of affiliation, the rupture at Old Westbury between students, faculty, and administration seems inevitable in hindsight. Major divisions had persisted from the planning phase; there was little concord on any issue. Some students sought refuge from the college by involvement in social movements outside the college—the Young Lords, the Women’s Liberation Movement, the strike at Ocean Hill-Brownsville. Others pushed for change within the college. Some faculty fled traditional institutions and sought a free-form educational model; others insisted on traditional teaching methods or the canon. Some students sought to define their education entirely on their terms, others, particularly students of color, demanded an education both rigorous and relevant. The President wanted the college to be a “school of the world,” and he attracted a global student body, and though he supported action-oriented Peace Corps-style component to education, he was also deeply enamored of the liberal arts, Great Books approach of the University of Chicago and St. John’s.

Administrators struggled to make the institution cohere. Two major concerns brought conflict to a head: students’ perception that “full partnership” meant their involvement in all aspects of college governance and their determination to diversifying the student body so that the majority of students were non-traditional students from communities of color. Administrators rejected both claims. A student sit-in of the President’s Office ultimately led SUNY to shut down the college in the Spring of 1970. The President left for a new presidency at Pennsylvania’s Bryn Mawr College. Students continued their educations, largely in study abroad programs. The College’s demise was “autopsied” in the national press, including in the New York Times, Esquire and Harper’s Magazine. That fall, SUNY charged a new President, John Maguire, with reconstituting the College.

Maguire, who had roomed with Martin Luther King at Crozer Theological Seminary as a young man, was himself a committed civil rights activist who was an early Freedom Rider against bus segregation; King consulted with Maguire on his famous 1967 anti-Vietnam speech at the Riverside Church. Maguire embraced students’ desire for a more inclusive student body and a commitment to social justice. The newly constituted college sought to enroll a student body reflective of the New York metropolitan area’s heterogeneity, particularly students “previously bypassed by higher education.” Its informal “30:30:30:10 plan” sought pluralism so that different demographic groups, African-American, Latino, White American, and Asian, had a presence in the college. When the college reopened in 1972, the first catalog also articulated a commitment to “culture learning,” or what today would be called “multi-culturalism,” to ensure students’ awareness of their engagement in a larger world. The College broke with its commitment to a fully experimental education that students helped design, though experimentalism was retained through innovative pedagogies, an interdisciplinary, departmental structure, and a community education commitment. An unusual mix of students committed to social justice continued to enroll as well.

Today, the College at Old Westbury, led by Dr. Calvin Butts, is ranked as the nation’s fourth most diverse liberal arts college. About one-third of the student body is African-American, twenty percent is Latino, and ten percent is Asian, primarily from South Asia; more than one in four are also the first in their families to take any college courses. Educational standards have risen alongside this growing heterogeneity. With over 17,000 alumni, the College at Old Westbury has nearly a fifty-year history as a vehicle propelling previously marginalized populations into the mainstream.

Bibliography

Peter Applebome, “The Accidental Giant of Higher Education” New York Times, July 23, 2010.

Gunapala Edirisooriya, “A Market Analysis of the Latter Half of the Nineteenth-Century

American Higher Education Sector,” History of Education (January 2009), 115-132.

John Dunn, “Old Westbury I and Old Westbury II, in Academic Transformation: Seventeen

Institutions Under Pressure, ed. by David Riesman and Verne Stadtman, (New York:

McGraw-Hill, 1973), 199-224.

Harry Forgeron, “Westbury Estate to be a College” and “Opulent Old Westbury Estate Scene of

Class Revolution.” New York Times, June 18, 1967.

Judith Glazer, “Nelson Rockefeller and the Politics of Higher Education in New York State,”

History of Higher Education Annual v. 9 (1989): 87-114.

Sanford Levine “The Empire State Creates a University,” in SUNY at Sixty: The Promise of the

State University of New York edited by W. Bruce Leslie, John B. Clark, and Kenneth O’

Brien (Albany: SUNY Press, 2010).

Gene Maeroff, ”A College Struggles to Recover on Long Island,” New York Times,

November 28, 1971.

Jay Neugeboren, “Your Suburban Alternative,” Esquire, September 1970.

Michael Novak, “Battles of Old Westbury,” New York Times, July 1, 1971.

Tod Ottman, “Forging SUNY in New York’s Political Cauldron” in SUNY at Sixty: The Promise of the

State University of New York edited by W. Bruce Leslie, John B. Clark, and Kenneth O’

Brien (Albany: SUNY Press, 2010).

Robert D. Parmet, Town and Gown: The Fight for Social Justice, Urban Rebirth, and

Higher Education (Lanham, MD: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2010).

Tom Powers, “Autopsy on Old Westbury,” Harper’s Magazine, September 1971.

“A Short History of SUNY” at https://www.suny.edu/student/university_suny_history.cfm,

accessed July 8, 2013.

Henry Steck, “Higher Education in New York State,” in The Oxford Handbook of New York

State Government and Politics, ed. by Gerald Benjamin (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2012), 662-711.

Patricia Strach, “Making Higher Education Affordable: Policy Design in Postwar America,”

Journal of Policy History (January 2009): 61-88.

SUNY College at Old Westbury, “Middle States Self Study,” 1975, “Middle States Self Study

for Accreditation,” February 2011, Office of Institutional Research, “Student Profiles,

Fall 2011” and “Parents’ Education FYE, Fall 2011.” archived at SUNY College at

Old Westbury Library.

John Thelin, A History of American Higher Education (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University

Press, 2011).

U.S. News and World Report (http://colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com/best-

colleges/rankings/national-liberal-arts-colleges/campus-ethnic-diversity), accessed

April 5, 2012.

Harris Wofford, “Creating Experimental Partners of a State University With Students as

Full Partners,” Paper before the UNESCO Meeting on New Models on Higher Education in

Asia and the America’s, January 1970.

Harris Wofford, “How Big the Wave,” in Five Experimental Colleges: Bensalem, Franconia,

Antioch-Putney, Fairhaven and Old Westbury, ed. by Gary MacDonald (New York:

Harper and Row, 1973).